web site for

Mare Kandre

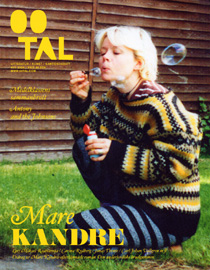

Mare Kandre published Bübins unge in 1987, at the age of 25. Previously, she had published two collections of prose-poetry. This was her first novel. But even here, the book was split up into short sections, almost resembling prose-poems, although there is now a plot to follow. I have divided these sections by an asterisk here, to save space. The photo is from roughly the same time as the novel was written, and was used as the cover of the Swedish literary magazine 00-tal, published in 2006. 00-tal had already published a Mare Kandre issue back in 1993, but this 2006 one was a memorial issue.

In her overview of Kandre's work, Helena Forsås-Scott describes the novel as follows:

"Here the first-person narrator is again a young girl. She is living with a woman and a man known as Bübin and Uncle, but these characters fade away as the central character’s physical growth and development begin to command all attention. As the central character begins to menstruate, the landscape becomes increasingly surreal, the grass standing to the height of tall reeds and the stalks of the nettles growing to the thickness of the trunks of young trees. In the midst of these threatening transformations, the central character now finds herself alone but for the Kid, who suddenly appears as the embodiment of the adolescent’s sense of split and alienation, small and innocent and cosseted by the adults as long as they have remained, the Kid becomes the butt of the confusion and anger raging in the older girl. The torture and killing of the Kid, presented as prerequisites for the adult phase of the central character’s life, convey the extent of the plight of the adolescent girl in this powerful text."

Summer has arrived –

In the sun everything is kindled and hard.

The trees are billowing sweetness, flies; the earth is silent; the wind stirs the bushes, the dense berry patches, up out of the grass, forcing the junipers up against the wall.

The tall grass reaches up to my thighs.

I’m standing far down, as if in deep water, and pushing aside the trees, pushing aside the bushes.

Because every day you go deeper into the narrow tunnel.

The colours become ever more muted. Sounds are muffled by the yellow water.

It comes nearer. It’s not as if the world is getting smaller, no: you’re going inwards, downwards, into the belly of the great heat –

You can hear stones splitting deep in the earth.

***

It’s Uncle, Bübin and me!

It’s just us –

You can’t really say what it’s like. I walk back and forth in the tall grass under the trees, moving the dry stones around distractedly with my foot.

Bübin’s face is shiny and greasy with sweat. I’m thinking about Uncle. In my ear I can hear a dry white sound, as if something is unfolding inside my head –

I go inside, sit with Bübin, I think the same strange hard thoughts over and over again –

It’s here; it isn’t here –

The stones lie wet and upturned behind me in the grass where I have walked, the dark side upwards. You can see where I have been. The evenings are falling ever later –

Then I go up to my room and sit on the bed, exhausted by all the heat, and can hear Uncle moving about in the room next door, heavy and groaning, as if he is dragging a large dead body back and forth across the floor.

***

Before summer came the trees stood grey and separate, a long way into June, July, as if it daren’t go there, not yet in bloom and withered like me!

The stones sat deep in the frozen earth, impossible to budge, and everything was wide open on account of the dry, yellow light, forced up and yellowed.

I stood at the well in my black coat.

Bübin could see me from the kitchen window. The road down to the village was blown bare and cleansed. I walked, my body hunched with cold. A few berries, frozen black still clung to the bushes. The cold grew more intense. The stones cracked –

This was before we got a pump.

There was water in the well –

It was the fault of the water.

It was when Uncle grew worse and something happened to his eyes, as there was something that would not grow pure.

Yes, we prayed so hard and powerfully in the evening that the prayers left a deep cavity behind in our sleep, but nothing was clarified.

I became ill and lay in bed next to Bübin.

My head was burst open by sweat in her large hand, and I slept a hard, crazy and yet permeable sleep, right across the whole spring.

I could hear Bübin walking in and out of the room, morn and night, but it wouldn’t loosen its grip on me. She would feel my closed face, and I calmly slept the fever out of my body, until the frost had left the ground like a thin, yellow smoke, and I emerged out of closed darkness, thin and worn –

My skin had grown taut.

I knew nothing about the world, no: I sat on a stool in the garden, wrapped up in Bübin’s shawls, and would grow faint and dizzy from just nothing at all!

Everything around me was undeveloped and dead.

But the grass stiffened, blade by blade –

Soon sprang up out of the frozen earth.

***

In the middle of the day, when it was hardest to walk around in the hot air, I am unwillingly following Bübin down to the village to shop –

As soon as we have started to walk between the low, silent wooden houses it grows dark, raw from the damp and the smells.

Bübin is walking in front. I am forced to run after her breathlessly to keep up with her, as if I was afraid she would leave me, be lost.

The houses stand a long way down into the ground, huddled together in a little hollow, and nothing can be heard, we pass no one.

It’s the large, black timbers of the houses that make everything so quiet. The forest pushes in. The village is slowly sinking into the blackish grey ground, house by house, I am wading through dung and filth and the smells make me dizzy and woozy, I have to push hair in mouth and keep on chewing.

The houses are leaning –

I run after Bübin out onto the market place and exhale the sour air. There we stand. I immediately grow light, the dizziness leaves my body.

An old woman is selling fish from large barrels, a tree with a black, sparse crown is growing here, wild and fumbling, as if it wants to leave, straight upwards and at once Bübin places two fish in my empty basket.

We walk between the various stalls –

Everyone knows who Bübin is, she fills my basket with pale, bitter greens, no larger than unripe fruit or stones, as nothing can grow to become sweet and big in the soil around the village, it simply lies there silent and hardened in the meagre shade under roots and grass.

Then we go off to a house on the market place and Bübin enters.

I wait outside with the full basket. I have not yet seen Ildre and Dordi. I sit on my hunkers and draw flowers in the soil –

Further down, a door to one of the old-fashioned houses suddenly opens.

Two men are carrying out a small, light coffin between them. Three women come out. I squat there with my fingers in the soil, watching –

The black tree begins to bend right away: agitated, afraid. I get a dead, harsh taste in my mouth, and the houses stand there dogged and small around the square, the trees stand and sway, it smells, and I want Bübin to come back right away!

I can hear people sitting in the cramped houses, but can’t make out what they are saying. The men, the three women, all look down at the ground in shame –

I turn around and see Bübin coming out of the house, slowly, and with renewed vigour in her step.

A pale child’s face pops up in the overgrown window, but glides away again –

I snatch my basket and run after Bübin, up out of the village.

Translated from Swedish by Eric Dickens